Starter Methods: Soft Starters vs Across-the-Line

Soft starters curb inrush and mechanical shock with adjustable ramp-up, while across-the-line offers cheaper, instant starts but higher stress and peaks.

Starter Overview — In the world of industrial motors, two foundational approaches dominate the conversation about how to get rotating machines up to speed: the across-the-line starter and the soft starter. Both methods energize the motor and produce torque, but they do so with very different impacts on electrical networks, mechanical systems, and operating budgets. Across-the-line, also known as direct-on-line, applies full line voltage immediately, prioritizing simplicity and ruggedness. A soft starter, by contrast, ramps voltage and limits inrush current, emphasizing smoother acceleration and reduced stress. Choosing between them involves understanding load characteristics, power system strength, control requirements, and lifecycle costs. The right decision balances factors like starting torque, voltage drop, mechanical wear, and maintenance expectations. This guide explains how each method behaves, where each shines, and what to consider when specifying equipment for pumps, fans, conveyors, compressors, and other common industrial applications. By the end, you will have a clear, practical framework for selecting the most effective starting solution for your motor-driven assets.

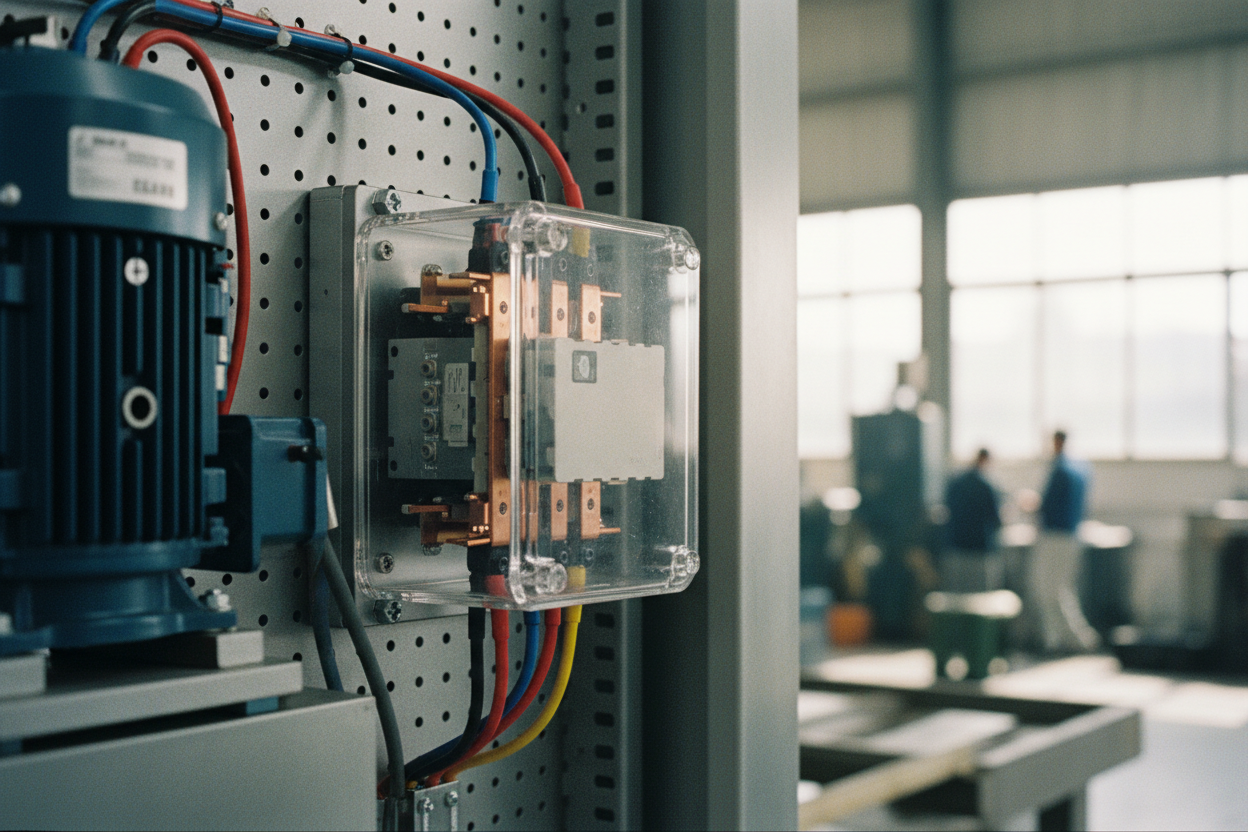

Across-the-Line Basics — The across-the-line method energizes the motor with full supply voltage the instant a contactor closes. That direct application produces rapid acceleration and high starting torque, making it attractive for stiff mechanical systems that can tolerate a strong initial jolt. The hardware is straightforward: a starter with overload protection and often a simple control circuit. Its strengths include low initial cost, compact footprint, and minimal configuration. However, the method draws current multiple times the motor's rated value during start, which can create voltage dips on weaker power systems and lead to nuisance trips or dimming effects elsewhere on the network. Mechanically, the sudden torque step can stress couplings, belts, gearboxes, and shafts, particularly in applications with fragile loads or frequent starts. Across-the-line is often favored when the electrical supply is robust, the process is not sensitive to torque shock, and the budget or maintenance strategy prioritizes simplicity over finesse.

Soft Starter Fundamentals — A soft starter uses solid-state devices, typically SCRs, to gradually increase the motor's applied voltage, thereby controlling starting current and torque. This controlled ramp-up reduces mechanical shock and minimizes electrical disturbances on the supply. Modern soft starters offer configurable ramp times, initial torque, current limit, kick-start for sticky loads, and soft stop to mitigate issues like water hammer in pumping systems. Many include a bypass contactor that short-circuits the SCRs once the motor reaches speed, reducing heat and losses during steady-state operation. The result is gentler motor acceleration, improved power system compatibility, and lower stress on connected equipment. Unlike a VFD (variable frequency drive), a soft starter does not provide continuous speed control; it focuses on controlled starting and stopping at line frequency. For applications where full-speed operation is desired after a smooth start, this approach provides an effective balance of control, efficiency, and cost.

Electrical Performance and Power Quality — The most visible electrical difference between methods is the inrush current profile. Across-the-line starting produces a steep current spike that can challenge upstream breakers, fuses, and transformer capacity, possibly inducing voltage drop that affects other loads. Soft starters shape the current, limiting its peak and spreading it over a longer starting interval. This improves coordination with protective devices and reduces the risk of nuisance tripping. During the ramp, SCRs in soft starters introduce some waveform distortion and heat, but this is transient and typically mitigated by a built-in bypass once the motor is at speed. Power factor during start may be lower for both methods, yet soft starters often reduce system stress simply by moderating the magnitude of current. For facilities with constrained power, multiple large three-phase motors, or strict power quality expectations, the smoother electrical signature of a soft starter can protect both the network and process continuity.

Mechanical Stress and Load Types — From a mechanical perspective, across-the-line starting is a punch. That instant torque can be beneficial when the load requires strong breakaway effort, such as some reciprocating machines or sticky conveyors. However, the same torque step can induce shock loads that accelerate wear in bearings, shafts, keys, couplings, and belt drives. By contrast, soft starters provide a gentle rise in torque, reducing mechanical stress and extending the life of connected equipment. This is especially helpful for pumps, where a smooth ramp reduces water hammer; for fans, where gradual acceleration limits airflow surges; and for conveyors, where controlled start prevents product spill or misalignment. High-inertia systems also benefit from current limiting that keeps thermal stress in check during extended acceleration. When starts are frequent, the cumulative impact of mechanical shock is significant, and a soft starter's controlled profile offers tangible savings in downtime, replacement parts, and alignment work.

Installation, Settings, and Control Integration — An across-the-line starter is straightforward to install: size the contactor and overload relay to the motor's full-load current, ensure proper short-circuit protection, and wire the control circuit. Soft starters require similar fundamentals plus attention to heat dissipation, enclosure ventilation, and proper bypass wiring when available. Correct sizing is critical; select based on motor current, starting duty, and ambient conditions. Commissioning focuses on tuning ramp time, current limit, and initial torque, using measured starts to verify that acceleration is smooth without exceeding thermal limits. Many soft starters offer inputs for PTC thermistors, programmable relays, and PLC integration for status and fault reporting. Both methods should include appropriate grounding, motor protection, and interlocks. For harsh environments, choose enclosures and conformal coatings that match conditions. With thoughtful setup, either solution can deliver reliable starting, but soft starters reward careful parameterization with better process control and equipment longevity.

Cost, Efficiency, and Decision Framework — Upfront, across-the-line starters typically cost less and are faster to deploy. Their efficiency in steady-state is inherently high because conduction losses are minimal, and the design is simple. Soft starters add initial cost and modest starting losses, but with bypass engaged, running efficiency remains strong. The economic case for soft starting often rests on reducing peak current, avoiding process upsets during start, and cutting mechanical wear that drives maintenance costs. Starting energy for both methods is similar for a given load, yet the soft starter's controlled profile can reduce demand-related impacts where such charges apply. If your process benefits from smoother acceleration, fewer failures, and improved power system harmony, a soft starter can return value quickly. If the load is robust, the supply is strong, and starts are infrequent, across-the-line may be ideal. For variable speed or tight process control, consider a VFD. Align the choice with electrical capacity, mechanical resilience, and lifecycle objectives.