Demystifying Credit Scores and Reports

Learn how credit scores are calculated, what appears on your reports, and smart steps to monitor, dispute errors, protect your identity, and raise your score.

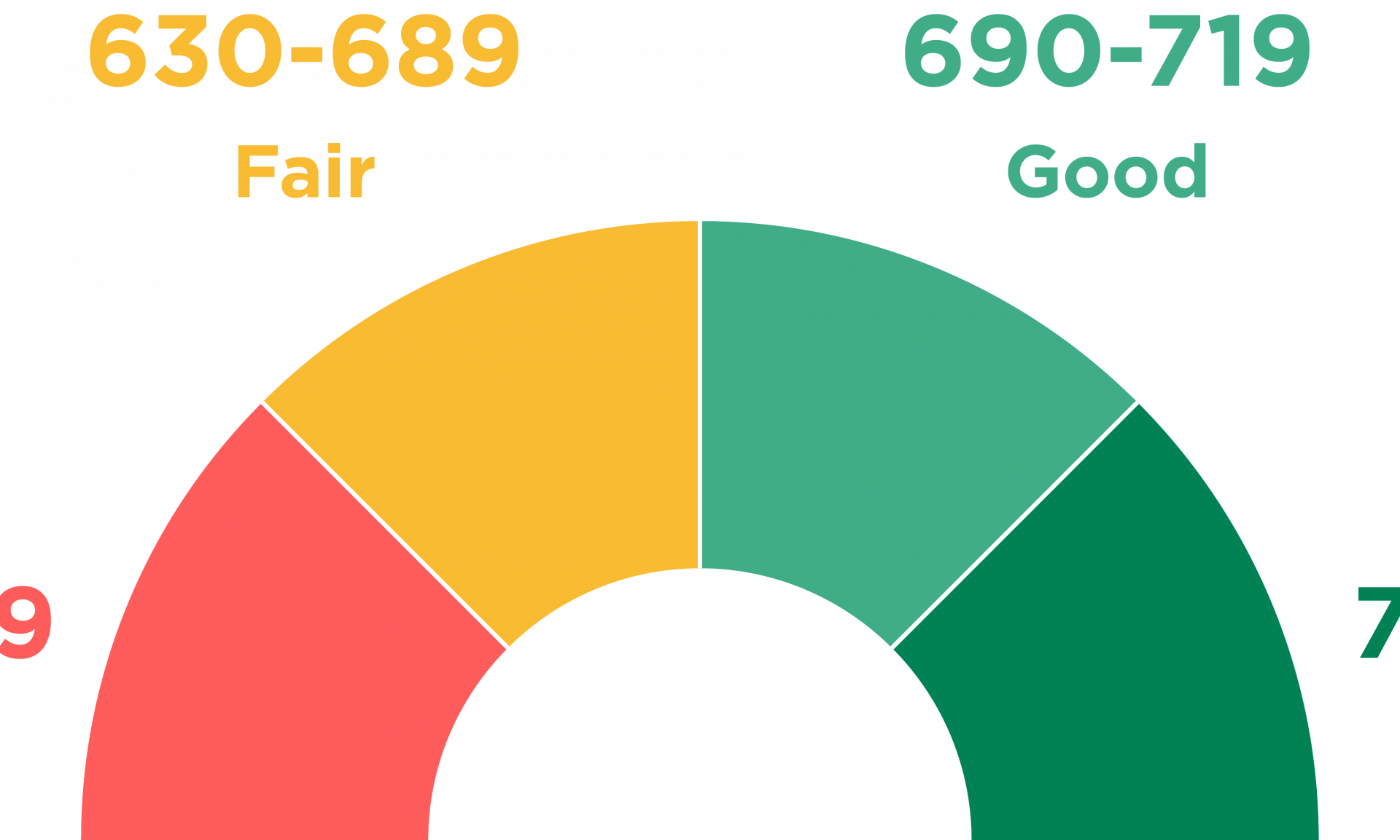

What a Credit Score Really Is: A credit score is a compact summary of your borrowing behavior, expressed as a single number that signals risk to lenders, landlords, and sometimes insurers. It is not a judgment of character; it is a statistical estimate of how likely you are to repay debt on time. Most scoring models look at five broad themes: payment history, credit utilization, length of credit history, new credit, and credit mix. Think of the score as a snapshot that updates as your habits evolve. Pay on time, keep balances modest relative to limits, and let accounts age, and the snapshot becomes more flattering. Miss payments, crowd limits, or open too many accounts too quickly, and the snapshot can dim. The practical payoff is tangible: better scores often translate into lower borrowing costs and wider approval odds, which can save substantial money over a lifetime. Treat it as a personal finance vital sign you can influence.

Inside Your Credit Report: Your credit report is a detailed file that records how you have used credit over time. It includes identifying information, a list of accounts such as credit cards, loans, and lines of credit, and key details like balances, credit limits, payment status, and dates opened. You will also see inquiries when companies access your report, along with records of late payments, collections, or other derogatory marks. Lenders, and sometimes landlords or insurers, use this report to evaluate your reliability. Creditors send updates to major credit bureaus on a regular schedule, so the report changes as your behavior changes. Accuracy matters because scores are generated from this data. Checking for errors, such as accounts that are not yours or payments misreported as late, is essential. Think of the report as the raw ingredients; your score is the recipe's result. Keep the data clean, and the outcome improves.

How Scores Are Calculated: While formulas differ, most models emphasize payment history as the most important factor, because it signals reliability. A single missed payment can weigh heavily, while a long streak of on-time payments steadily strengthens your profile. Next comes credit utilization—the ratio of your revolving balances to your total credit limits. Lower utilization generally signals lower risk; many people aim for a figure well below half, with even lower being better. Length of credit history reflects the average age of your accounts, rewarding patience and stability. New credit considers recent hard inquiries and openings, which can temporarily dip a score if excessive. Finally, credit mix reflects the variety of accounts, such as credit cards and installment loans, showing you can manage different obligations. No single factor tells the whole story; the model looks at the pattern. Consistency, moderation, and time are the quiet levers that move scores upward.

Steps to Build and Improve: Improving your score is less about hacks and more about steady habits. Start with on-time payments; automate at least the minimums to avoid slipups, then pay in full to control costs. Address credit utilization by paying down balances, making multiple payments during a cycle, or requesting a higher limit if your budget and discipline support it. For thin files, consider a secured card, becoming an authorized user on a well-managed account, or responsibly adding a small installment loan you can comfortably repay. Dispute genuine errors on your report with clear documentation, and follow up until they are resolved. If you are rebuilding after setbacks, focus on a single primary card, keep expenses predictable, and let good behavior compound. Resist closing long-standing accounts without a strategy, and avoid rapid account hopping. Building credit is cumulative; small, repeatable actions add up to meaningful progress over time.

Using Credit Strategically: Credit can be a tool when used intentionally. Align credit with a budget and a purpose: convenience, protection, and rewards are helpful when you pay on time and keep balances low. Plan significant purchases in advance, ensuring you can absorb them without straining utilization. Keep older accounts active with light, regular use to preserve account age. Be mindful of hard inquiries—each application can slightly affect your score—so cluster necessary applications thoughtfully and avoid impulsive ones. Understand soft inquiries; checking your own report or receiving prequalification offers does not affect your score. If carrying a balance is unavoidable, prioritize higher-rate debts and avoid spreading balances across many cards. Use alerts to track due dates and unusual activity, and review statements for accuracy. Strategic credit use is about control and foresight: you decide when to leverage credit, why it benefits you, and how to keep risk in check.

Monitoring, Security, and Fraud: Regular credit monitoring is an essential defensive habit. Schedule periodic reviews of your credit reports to spot errors early, track progress, and catch warning signs of identity theft, such as unfamiliar accounts or unexplained inquiries. Consider setting alerts that notify you when balances spike or new accounts appear. If you suspect misuse of your information, place a fraud alert or consider a credit freeze to prevent new openings while you investigate. Document every step, save correspondence, and follow up consistently until issues are resolved. Protect personal data by using strong, unique passwords, enabling multifactor authentication, and avoiding oversharing sensitive details. Shred documents containing personal identifiers, and be cautious with public Wi‑Fi when accessing financial accounts. Security is not a one-time task; it is a routine. The more you tighten your perimeter and review your reports, the faster you can respond and minimize damage.

Common Myths Debunked: Several persistent myths can derail smart credit decisions. Checking your own score or report is a soft inquiry and does not harm your profile. Income does not directly affect your score; the model measures credit behavior, not earnings, though income influences what you can responsibly repay. You do not need to carry a balance to build credit; paying in full shows strong management and avoids interest costs. Closing old accounts can reduce average age and available credit, potentially raising utilization; consider alternatives before you close. Paying off collections may not immediately erase them from a report, but it can improve your standing and helps future evaluations. Rate shopping for one type of loan within a focused window is often grouped as a single event in many models, encouraging smart comparison. Finally, good credit is not reserved for the lucky; it is built through predictable actions performed consistently.

Designing a Long-Term Strategy: Treat your credit profile as part of a broader financial plan. Set clear goals—qualifying for a mortgage, reducing borrowing costs, or strengthening negotiating power—and reverse engineer the behaviors that support them. Automate payments, earmark cash flow to lower utilization, and maintain a durable emergency fund to avoid relying on credit during surprises. Build a sensible credit mix only when it fits your needs; never take on accounts solely for points or vanity. Measure progress with periodic score checks and report reviews, noting trends rather than obsessing over small fluctuations. If you stumble, respond quickly: communicate with creditors, create a catch-up plan, and document every agreement. Credit is a long game where patience and discipline are rewarded. By aligning daily actions with your goals, you transform your score and report from abstract metrics into practical tools that save money, expand options, and support financial resilience.